Twenty Lawyers Against the Implementation Gap

Linklaters hires 20 practising lawyers, not technologists, to bridge the gap between AI infrastructure and real workflow change. Firms falter less from missing tools than missing people who turn them into behaviour. Volume isn’t adoption; implementation is the real test.

Linklaters has created a twenty-strong AI lawyer team. Not innovation consultants. Not technologists. Practising lawyers whose full-time job is closing the gap between AI infrastructure and actual workflow change.

I see this move differently than most observers celebrating another firm's AI investment.

This is an experiment to discover whether dedicated implementation capacity can solve what better tools haven't: getting lawyers to actually change how they work.

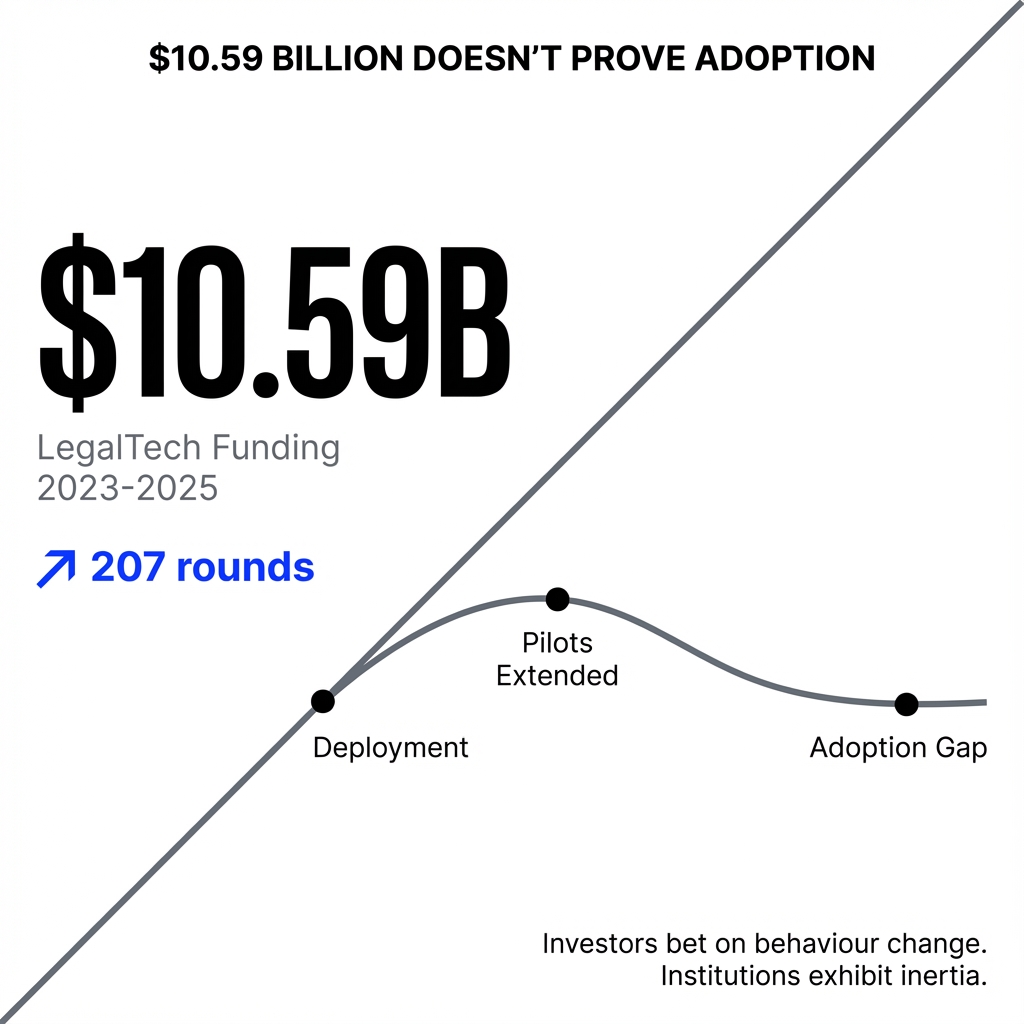

Query Volume Isn't Adoption

Linklaters already runs Laila, their internal chatbot. With impressive usage statistics in the main stream legal press.

But query volume tells you nothing about workflow integration.

Lawyers asking an AI for help still work the old way. They remember to query a tool when convenient. The fundamental process remains unchanged.

The gap sits between occasional tool usage and embedded workflow redesign.

These twenty lawyers need to map AI capabilities onto specific behavioural patterns in each practice area. The translation runs from "here's a chatbot" to "here's how corporate lawyers should structure due diligence differently because AI exists."

That's a different challenge entirely.

The Mechanism Problem

You can't tell a partner who's done due diligence the same way for fifteen years to change their behaviour. That approach fails every time.

The mechanism these AI lawyers need works differently.

Take an actual due diligence process from a practice area. Rebuild it with AI embedded at specific friction points. Prove it's faster, more thorough, or less risky.

Show partners their own process, but demonstrably better, backed by evidence.

The credibility comes from these lawyers understanding why the partner does it that way in the first place. They're not proposing changes that ignore institutional reality. They work within the behavioural tolerance of existing workflows rather than attempting wholesale replacement.

Most firms fail because nobody's full-time job is closing the implementation gap.

What Evidence Would Prove This Works

I need to see measurable behaviour change, not deployment metrics.

The evidence: Are corporate partners actually running due diligence differently six months after the demonstration? Can you track that the new process gets used repeatedly, not just tried once?

The failure mode is demos that receive polite applause but don't change Tuesday morning's workflow.

I'd look for sustained usage data on redesigned processes. How many matters use the new approach? How consistently? Does it spread to other partners without the AI team constantly selling it?

If adoption becomes organic because the process genuinely reduces friction, you've succeeded. If you still need twenty lawyers evangelising after a year, you've built something that doesn't embed properly into existing behavioural patterns.

The Business Model Tension

Here's the structural problem nobody wants to discuss openly.

You can't have twenty lawyers optimising for efficiency whilst four hundred lawyers are incentivised to maximise hours. Substantial portions of hourly billable tasks have automation potential.

The only resolution: the AI lawyer team focuses on client-facing solutions that generate revenue differently.

Build AI capabilities that become service offerings clients pay for separately, not just internal efficiency tools. The broader firm keeps billing traditionally whilst this team explores alternative value models.

But that only works if clients want to pay for AI-enhanced services rather than expecting efficiency gains to reduce their bills.

I haven't seen anyone consistently pull off that repositioning yet. Most clients view AI as the firm's efficiency problem, not something deserving a premium.

The repositioning works only if the AI capability delivers something genuinely unavailable through traditional methods. Contract analysis at previously infeasible scale. Due diligence that catches risks human review systematically misses.

You're selling a different outcome, not the same outcome delivered more efficiently.

Partial Success Is the Likely Outcome

Based on patterns I've observed, Linklaters will probably close the implementation gap in two or three specific practice areas. They'll find partners willing to genuinely collaborate. The AI capability will deliver measurable value clients recognise.

Firm-wide transformation? Unlikely.

The structural barriers don't disappear because you've allocated dedicated capacity.

Billable hour incentives persist. Partner autonomy remains. Client expectations about pricing continue.

What twenty lawyers can do is prove the concept works in contained environments with the right conditions. They'll identify which types of legal work actually benefit from AI integration in ways that justify implementation cost.

They'll also discover which applications are just efficiency theatre.

The real question isn't whether Linklaters transforms entirely. It's whether they learn enough to know where AI implementation genuinely creates value versus where it's expensive optimism.

How to Evaluate This Properly

The evaluation framework needs to match the actual challenge, not the marketing narrative.

Ask three specific questions:

First: Can you identify concrete processes that changed and stayed changed? Not pilots. Actual operational workflows that multiple partners now use differently six months after implementation.

Second: Did those changes generate measurable value that clients recognised? Either through willingness to pay differently or through documented risk reduction.

Third: What did Linklaters learn about where AI implementation fails? Are they honest about publishing those findings?

Most firms only discuss successes and hide failures. That means they're not actually learning.

Real success looks like evidence-based clarity about what's achievable. If Linklaters produces a candid assessment saying "AI integration worked in these two contexts for these specific reasons, failed in these four contexts for these structural reasons, and here's what that tells us"—that's success, even without transformation.

The failure mode: claiming victory based on deployment metrics, usage statistics that don't distinguish trial from adoption, or client testimonials that don't translate into changed purchasing behaviour.

Firms with a clear strategy are more likely to see ROI from AI than those adopting without strategy. But those ROI claims rarely specify whether they're measuring deployment or genuine adoption.

The Market Pressure Reality

The legal industry isn't ready for honest evaluation because the incentives don't reward it.

Linklaters will face pressure from clients wanting reassurance their law firm is "AI-ready." From competitors claiming transformation regardless of evidence. From their own partnership needing to justify the investment.

Market pressures favour declarative statements about AI leadership over nuanced assessments of what actually worked.

Even if the twenty lawyers produce rigorous findings about where implementation succeeded and failed, the public narrative will likely be sanitised. "Linklaters successfully integrates AI across practice areas" rather than "we learned AI works in these two contexts and fails in these four for structural reasons."

The honest evaluation might exist internally. But publishing it requires admitting limitations in a market that penalises honesty about what doesn't work.

My expectation: they'll frame whatever they achieve as vindication of the approach, even if evidence suggests more modest conclusions.

That's not dishonesty. That's survival in a market that doesn't yet value evidence-based clarity over aspirational positioning.

The change needs to come from clients. When clients start requiring firms to demonstrate sustained usage data, show specific workflow changes producing documented value, and explain honestly where AI implementation failed and why—then the market will reward evidence-based clarity.

Until then, even rigorous implementations get forced into optimistic framing that obscures the actual lessons learned.

Linklaters has allocated enough capacity to finally discover whether the implementation gap is closable with dedicated resources, or whether deeper structural barriers exist that more lawyers won't solve.

The answer matters more than the marketing narrative around it.