Where Ten Billion Dollars Went and What It Actually Proves

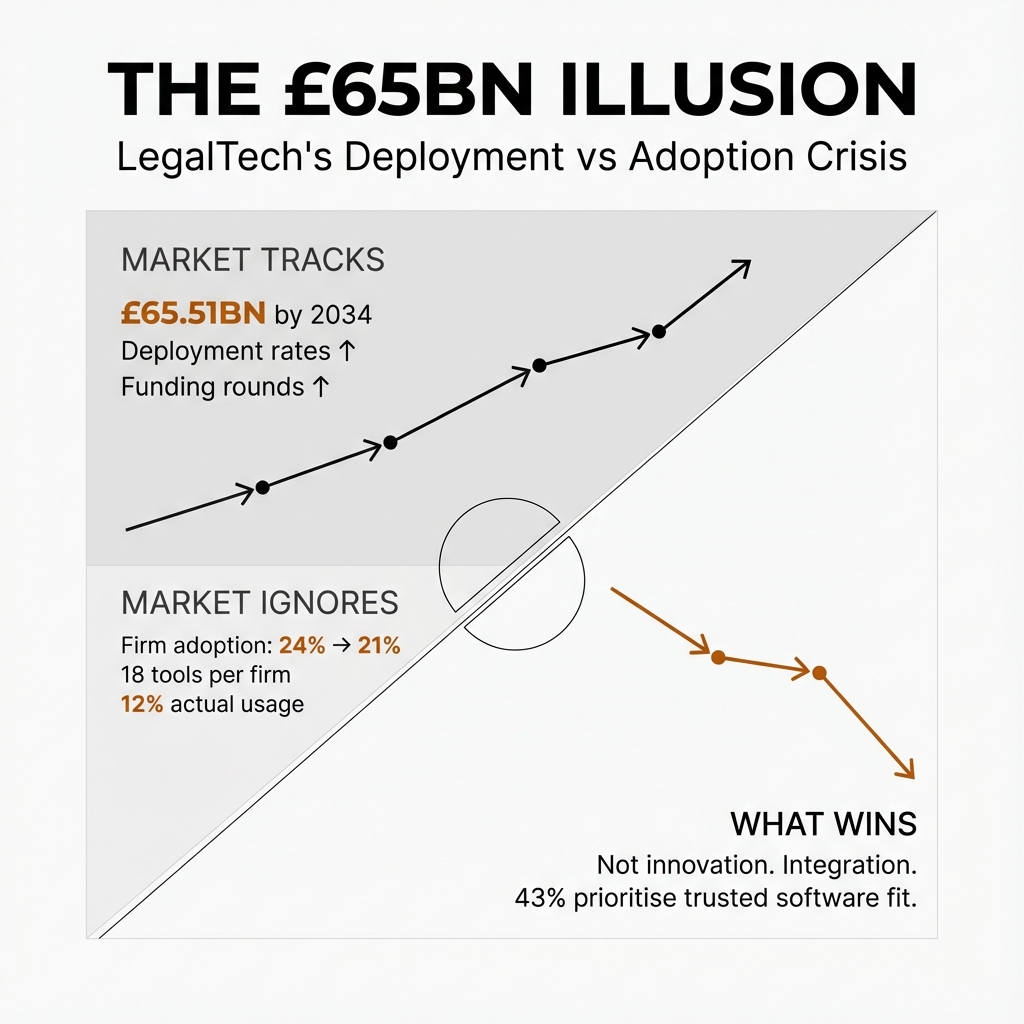

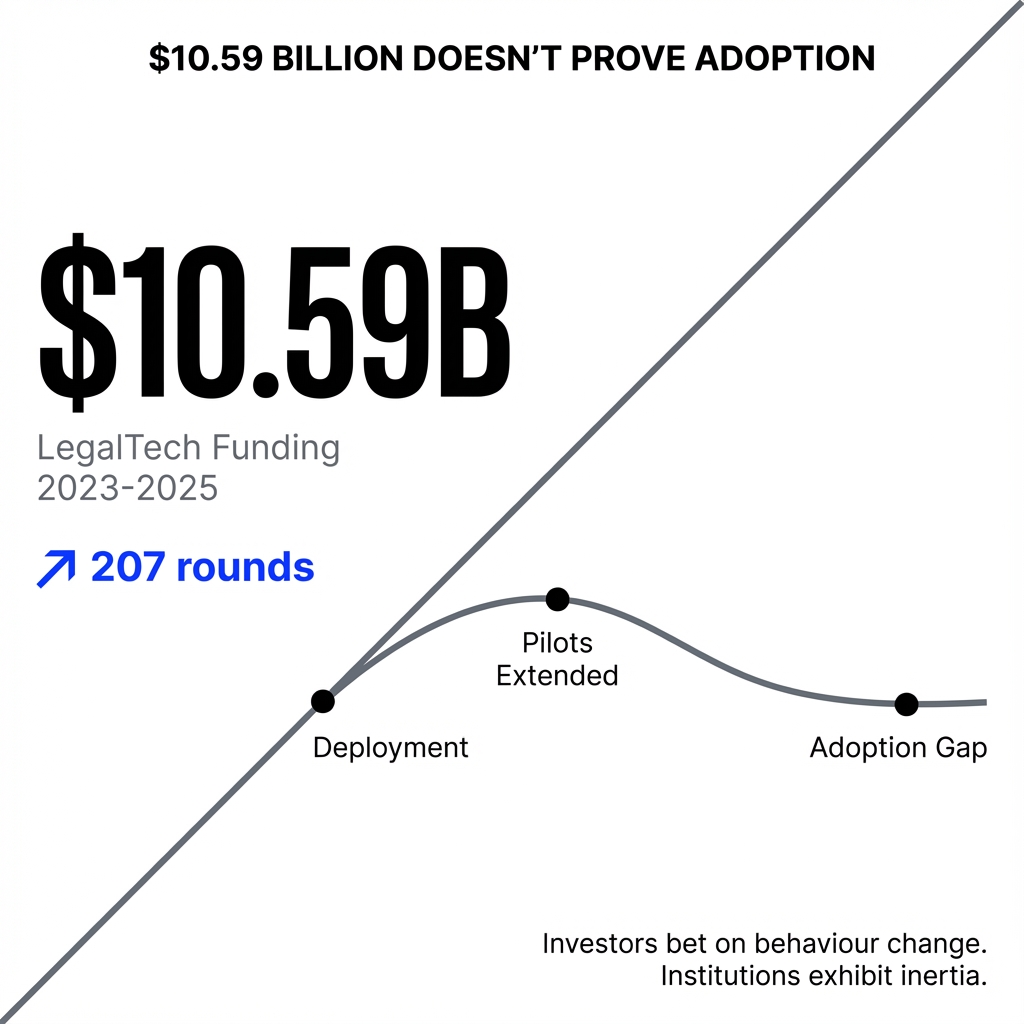

Between 2023 and 2025, investors poured $10.59 billion into LegalTech across 207 funding rounds. Harvey went from $80 million to an $8 billion valuation. Clio raised $900 million. EvenUp hit unicorn status. The funding announcements read like validation that AI-native legal platforms have arrived.

Between 2023 and 2025, investors poured $10.59 billion into LegalTech across 207 funding rounds. Harvey went from $80 million to an $8 billion valuation. Clio raised $900 million. EvenUp hit unicorn status. The funding announcements read like validation that AI-native legal platforms have arrived.

But funding announcements measure investor confidence, not institutional adoption.

The gap between those two things—between capital allocation and operational reality—reveals something uncomfortable about what this $10.59 billion actually proves. Investors are pricing in future behavioural change at legal institutions that exhibit extreme procedural inertia and risk aversion. They're betting that lawyers will adapt to technology rather than requiring technology to adapt to existing behavioural infrastructure.

Every pattern in institutional legal behaviour suggests they're betting on the wrong model.

The Valuation Compression That Proves Nothing About Adoption

Harvey's trajectory from $80 million in 2023 to $8 billion in 2025 demonstrates investor belief in AI-native legal platforms as a structural shift. That compression validates that the problem Harvey addresses is real and the market opportunity is massive.

What it doesn't validate is that institutional legal environments have actually absorbed this technology into their operational reality.

Harvey reports "firmwide usage rates topping 90 percent" with retention metrics placing it "amongst the top performers in enterprise software." But industry observers noted "2024 being the year of pilots, which extended into 2025" with predictions that "2025 would be the year of adoption."

The language reveals the gap. Pilots extending into their second year aren't adoption—they're extended evaluation periods where deployment happened but embedding didn't.

Harvey dedicates roughly 10% of its team to ex-lawyers in customer success roles who drive change management, implementation, and adoption within law firms. They exist to ensure clients hit utilisation thresholds needed for renewal.

That's not evidence of frictionless adoption. That's evidence that even the most-funded AI-native platform requires substantial human intervention to bridge the deployment-to-adoption gap.

The funding announcements don't show post-deployment usage data. You don't see metrics on how many lawyers actually use Harvey daily versus how many firms purchased access. You don't see retention rates after the initial deployment period. You don't see evidence of workflow integration—whether Harvey embedded into existing procedural infrastructure or sits alongside it as an optional tool with inconsistent usage.

Capital is pricing in future behavioural change at legal institutions, not validating that the change has occurred at scale.

The Timeline Optimism That Underestimates Institutional Inertia

The $10.59 billion reflects genuine belief that legal institutions can't maintain current operational models indefinitely. That belief isn't irrational.

But the funding pattern suggests investors are pricing in a three-to-five-year adoption curve when the actual embedding timeline for risk-averse professional environments might be seven to ten years.

That gap between expected and actual adoption velocity is where the underestimation lives.

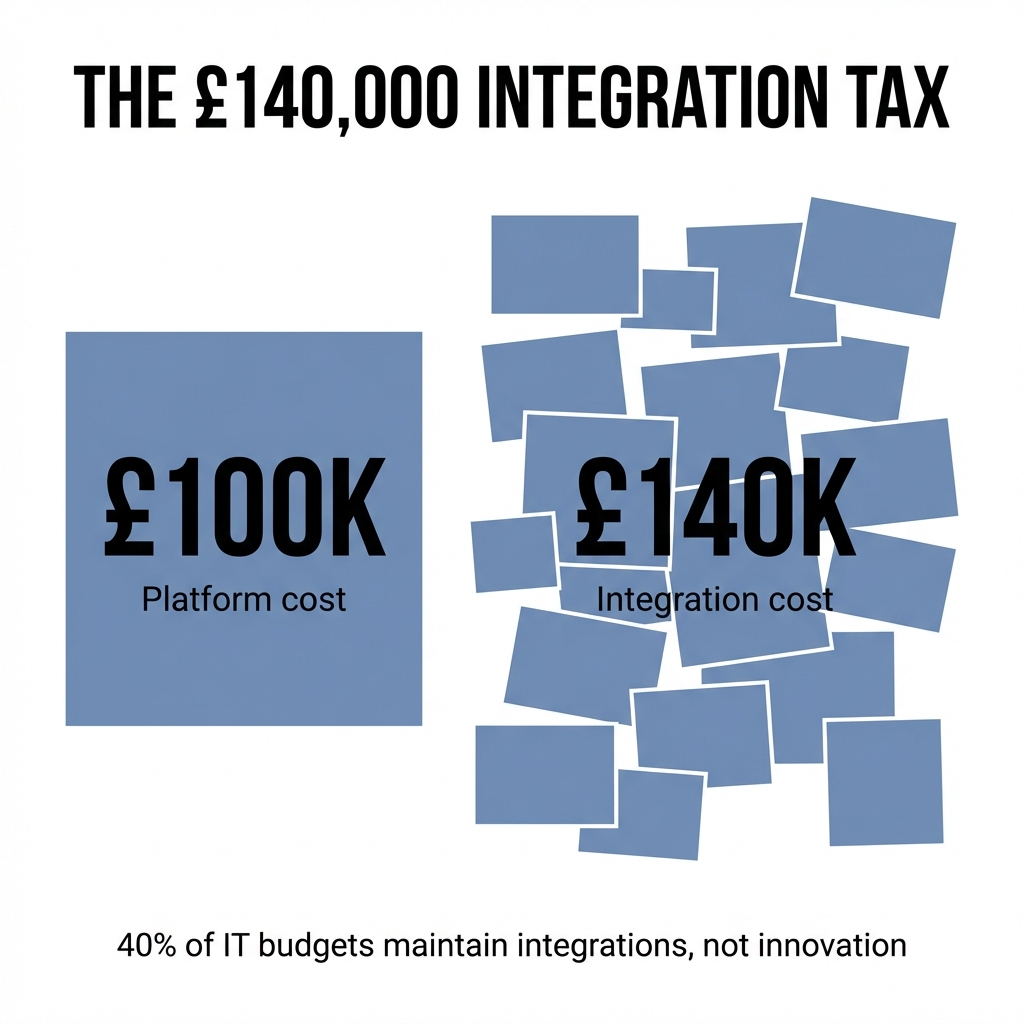

78% of US law firms weren't using any AI tools at all as of year-end 2024. American firms with 51 attorneys or more are using AI at roughly double the rate of firms with fewer lawyers. AI adoption correlates with capital capacity rather than functional superiority.

The market is funding solutions that require institutional change whilst systematically underweighting the procedural and psychological infrastructure that has to shift before these tools can embed.

Only 22% of law professionals believe they've received adequate training on their company's tech. The American Bar Association study in 2020 showed only 22% of those surveyed strongly agreed they had received adequate training on their firm's technology.

Deployment happens without the behavioural embedding infrastructure required for sustained adoption.

Investors see technical capability and efficiency gains on paper, then extrapolate adoption. But they're not adequately pricing in the cost of behavioural change—the retraining, the workflow redesign, the cultural resistance, the regulatory uncertainty, the partnership structure implications.

The funding isn't wrong about the destination. It's optimistic about the journey.

That optimism creates a secondary problem. It pressures funded companies to show growth metrics that look like adoption but might just be deployment. Firms buying access versus lawyers actually using the tools daily. That pressure to demonstrate traction leads to exactly the kind of deployment-as-success thinking that doesn't serve long-term embedding.

Practice Management's Camouflaged Adoption Story

Clio's $900 million round at $3 billion valuation reflects something closer to proven adoption. Practice management platforms have demonstrable embedding because they've become operational infrastructure for small and mid-sized firms.

They're not optional tools. They're where the work lives.

Billing, matter management, client communication—these aren't adjacent to workflow, they are the workflow. Clio has grown revenue beyond $200 million ARR and serves more than 1,000 mid-sized firms in the United States alone.

But practice management platforms benefit from lower behavioural friction because they're replacing genuinely painful manual processes. Time tracking in spreadsheets, paper-based matter files, email chaos—the existing state is so obviously inadequate that adoption resistance is lower.

The friction cost of change is offset by immediate, tangible pain relief.

That's a different adoption equation than AI-native platforms, which ask lawyers to change how they think and work, not just digitise what they're already doing.

Clio's valuation reflects real adoption, but it's adoption in a context where the behavioural change required was minimal. It's digitisation, not transformation.

The risk is that investors look at practice management adoption rates and assume AI-native platforms will follow similar curves. They won't. The cognitive and procedural change required is categorically different.

Practice management platforms often report user numbers that conflate firm-wide licences with active daily usage. A firm might have Clio deployed across 50 lawyers, but actual sustained usage might concentrate in 15. The platform still gets credited with 50 "users" in growth metrics.

That's deployment penetration, not behavioural embedding depth.

European Emergence as Pattern-Matching, Not Adoption Advantage

The narrative around European LegalTech emergence focuses on GDPR, data sovereignty, and regulatory complexity creating demand for localised solutions. That's partially true, but it's more justification than driver.

What actually happened is that European investors watched US LegalTech valuations accelerate and decided they needed exposure to the category.

The geographic concentration reflects capital seeking category participation, not evidence that European legal institutions are somehow more adoption-ready than their US counterparts.

European legal markets exhibit even stronger procedural conservatism than US markets in many contexts. The partnership structures are older, the hierarchies more entrenched, the technology adoption curves historically slower.

The idea that these environments will suddenly prove more receptive to AI-native platforms doesn't hold up against observed institutional behaviour.

Where there might be genuine structural advantage is in the fragmentation itself. European legal markets are linguistically and jurisdictionally fragmented, which creates natural barriers to US platform dominance. That fragmentation opens space for regional players.

But it also multiplies the adoption challenge.

A tool that works in UK legal workflows might not translate to German or French procedural infrastructure without significant adaptation. The funding is going into a more complex adoption environment, not a simpler one.

European legal AI funding is heavily concentrated in document review and contract analysis—tasks that are procedurally similar across jurisdictions even if the underlying law differs. Investors are betting on workflow universality, but they're underestimating how much institutional adoption depends on cultural comfort, not just functional capability.

A technically excellent German contract AI still has to overcome the same behavioural embedding challenges as a US equivalent, plus additional regulatory scrutiny and data localisation requirements.

Specialist Investors Bring Patience, Not Better Adoption Metrics

When Thomson Reuters commits $150 million to a corporate venture fund in LegalTech, they're not making a pure financial bet like traditional VC. They're making a strategic positioning bet.

Thomson Reuters has incumbent distribution, existing client relationships, and integration pathways that pure-play investors don't have. Their capital validates that they see LegalTech innovation as either complementary to their existing offerings or threatening enough that they need exposure to it.

That's a different signal than venture capital chasing category returns.

The LegalTech Fund raising $110 million for Fund II validates that there's enough demonstrated activity in the sector to support specialist investment vehicles. That's a maturity indicator.

But it doesn't mean they're applying more rigorous adoption scrutiny than generalist VCs.

Specialist funds can actually be more susceptible to category enthusiasm because their entire thesis depends on LegalTech succeeding.

They can't diversify away from the sector, so they're incentivised to be optimistic about adoption timelines.

What institutional capital does bring is longer time horizons and potentially more patience for the actual embedding process. Thomson Reuters isn't looking for a three-year exit. They're thinking about ten-year market positioning.

That patience could align better with realistic adoption curves, but only if they're actually measuring adoption rather than deployment.

The risk is that specialist investors bring domain expertise about legal markets but not necessarily about technology adoption mechanics in risk-averse environments. They understand the legal industry, but that doesn't mean they understand the behavioural infrastructure that determines whether a technically sound solution actually embeds.

They might be better at identifying real problems and evaluating legal domain fit, but equally vulnerable to underestimating the friction cost of institutional change.

The Acceleration From 40 to 94 Rounds: Momentum, Not Maturity

What happened between 2023 and 2025 is that a few high-profile rounds created proof points that LegalTech could command serious valuations. That wasn't proof of adoption at scale, but it was proof that investors were willing to price these companies aggressively.

Once that pricing precedent exists, capital floods in.

The acceleration from 40 to 94 rounds reflects capital availability and category momentum more than it reflects a doubling of genuinely adoption-ready solutions.

You can see this in the funding distribution. The massive rounds—Harvey's $760 million, Filevine's $400 million, Clio's $900 million—capture the majority of the capital. But the acceleration in round count comes from seed and Series A rounds for companies that are still pre-adoption proof.

They're getting funded on category association and technical capability demonstrations, not on evidence of institutional embedding.

LegalTech became a defined investment category rather than a niche within broader enterprise software.

Once you have specialist funds, corporate venture arms, and established valuation comps, the category becomes self-reinforcing. Founders know they can raise capital in LegalTech, so more companies get started. Investors know other investors are active in the space, so they need exposure to avoid missing out.

That's category momentum, not adoption validation.

The 2023 baseline of 40 rounds probably represented companies with some demonstrated traction or unique technical capability. The expansion to 94 rounds includes those genuinely maturing solutions, but it also includes substantial capital going into earlier-stage companies betting on the category thesis rather than proving adoption mechanics.

It's the difference between funding following evidence and funding creating its own momentum.

The Missing Evidence: What Adoption Actually Looks Like

Early-stage companies should be showing post-deployment usage metrics, not just deployment counts. Specifically: daily active usage rates, feature utilisation depth, workflow integration evidence, and retention after the initial contract period.

But they're not being asked for this because investors are optimising for growth signals that are easier to demonstrate—pipeline, logos, contract values—rather than adoption signals that take longer to materialise.

What's missing is granular behavioural data.

How many users who have access actually log in daily? Of those who log in, how many are using the tool for core workflow tasks versus peripheral experimentation? What's the time-to-habitual-use curve? How long does it take from deployment to the point where users would actively resist having the tool removed?

Those metrics reveal actual embedding, but they require sustained observation periods that don't fit early-stage funding timelines.

The other missing evidence is workflow displacement proof. Is the tool replacing an existing process, or is it adding a new step that users have to remember to execute?

Replacement is adoption. Addition is overhead.

Early-stage companies should be demonstrating that their solution has become the path of least resistance for a specific task, not just an available option. But proving displacement requires before-and-after workflow analysis that most companies aren't conducting and investors aren't demanding.

They should also be showing adoption heterogeneity data—which user types adopt quickly versus slowly, and why. If only the most tech-forward 20% of a firm's lawyers are using the tool six months post-deployment, that's a red flag about institutional fit.

But if usage is spreading from early adopters to the middle majority, that's genuine adoption momentum.

Most companies report aggregate user numbers that obscure this distribution.

The final missing piece is friction documentation. What are the actual barriers to adoption that emerged post-deployment, and how were they resolved?

Companies that can articulate specific friction points and demonstrate how they reduced them are showing adoption literacy. Companies that just report growing user counts without acknowledging friction are either not measuring it or not experiencing it because usage is too shallow to generate meaningful resistance.

Either way, it's not proof of embedding readiness.

Document AI's Perfect Vanity Metric

"Documents processed" sounds like usage evidence but it's actually just throughput.

Processing 10,000 contracts tells you nothing about whether the output was trusted, acted upon, or integrated into decision-making workflows. It's activity measurement masquerading as adoption proof.

Document AI and contract analysis benefit from quantifiable output that creates the illusion of validation. A document gets analysed, data gets extracted, a summary gets generated—there's a tangible artefact that can be counted.

But the critical adoption question isn't whether the document was processed.

It's whether the human on the other end changed their behaviour based on that processing.

Did they stop manually reviewing the contract because they trust the AI output? Did they reduce the time spent on due diligence because the extraction was reliable? Or did they process the document through the AI and then do their traditional review anyway because they don't trust it enough to change their workflow?

Contract analysis is particularly susceptible to this because it can be positioned as a parallel validation layer rather than a workflow replacement. A firm can run contracts through an AI tool and still have associates do full manual review, then claim they're "using AI" when they've actually just added a step without displacing any existing work.

That's deployment without adoption, but it generates impressive document processing metrics.

Most law firms are currently using generative artificial intelligence tools, but adoption is occurring through pilots rather than firm-wide deployment. 80% of respondents say their firms are using or exploring generative AI in 2025, including all firms with 700 or more attorneys.

Yet only 40% of firms using Westlaw AI-Assisted Research have fully deployed the tool to lawyers. Only 36% of firms using the time platform Laurel.AI have it fully deployed.

"Using or exploring" conflates pilot programmes with genuine adoption.

What document AI companies should be measuring but largely aren't is workflow displacement rate and trust escalation curves. How long does it take before users stop double-checking the AI output? At what point does the tool become the primary method rather than the validation layer?

How many users are actually changing their work patterns versus how many are just running documents through the system to satisfy a partner's directive to "use the new tool"?

Those are adoption metrics. Document counts are deployment metrics dressed up as usage proof.

The Correction That Won't Look Like a Crash

There won't be a dramatic crash. That's not how this plays out in enterprise software categories with long sales cycles and institutional customers.

What we'll see instead is a slow-motion sorting process that looks like market maturation but is actually adoption failure being absorbed and redistributed.

The most likely pattern is strategic consolidation where well-capitalised players acquire struggling companies at significant discounts to their last funding rounds. That consolidation will be framed as market maturity and category leadership emerging.

But what it actually represents is capital-rich companies buying deployment footprints and customer lists from companies that couldn't convert deployment into sustained adoption.

The capital does create enough momentum for companies to survive on deployment metrics for longer than they should, but survival isn't the same as success.

You'll see companies maintaining revenue growth through new customer acquisition whilst existing customer adoption remains shallow. They'll hit renewal cycles where deployment-without-adoption becomes visible—customers who don't renew because the tool never embedded, or who downgrade their licences because actual usage was a fraction of purchased seats.

But here's why there won't be a clean correction: the companies with the most capital can afford to subsidise the adoption gap.

They can invest in customer success teams, extended onboarding, workflow consulting—essentially paying for the behavioural change process that should have been priced into the adoption thesis from the beginning. Well-funded companies can brute-force their way through the embedding challenge by throwing resources at friction reduction.

That works, but it's expensive and it means the unit economics don't look like software—they look like consulting with a software component.

The correction will hit hardest at the companies that raised on deployment metrics but don't have enough capital to fund the actual adoption process. They'll face a crunch where they can't demonstrate enough genuine usage to raise the next round, but they also can't afford the customer success investment needed to drive real embedding.

Those companies will stall or fail, but it'll be attributed to execution problems or market timing rather than to the fundamental measurement gap that allowed them to raise in the first place.

High-profile failures will happen, but they'll be attributed to execution issues, competitive dynamics, or "market timing" rather than to the fundamental measurement gap that allowed them to raise capital on deployment metrics in the first place.

Patent and IP Tools: Systematised Workflows Don't Guarantee Easy Adoption

Patent and IP tools sit somewhere between genuine adoption advantage and the next frontier for the deployment-versus-adoption pattern to repeat itself.

The adoption advantage in patent and IP is real but narrow. Patent prosecution workflows are highly procedural—prior art searches, claim drafting, office action responses—and they're already technology-adjacent because patent professionals are accustomed to working with databases and search tools.

That existing comfort with technology-mediated workflows reduces one layer of friction.

But systematised workflows don't automatically mean low adoption friction if the tool requires changing how decisions get made.

A prior art search tool that returns results faster is an easy adoption—it's the same workflow, just more efficient. But an AI tool that suggests claim language or predicts patentability is asking for trust in machine judgement on high-stakes decisions.

That's a different adoption challenge, and systematised workflows don't reduce it.

Patent and IP work, whilst procedural, is also deeply expertise-driven. Patent attorneys build their value on judgement, not just process execution. Tools that automate process steps are adoptable. Tools that appear to automate judgement face resistance because they threaten professional identity.

You get the same adoption heterogeneity you see elsewhere—junior attorneys adopt quickly because they're still building expertise, senior attorneys resist because the tool feels like it's encroaching on their domain authority.

What's actually happening with patent and IP funding is that investors see a category with clear pain points and they're betting that systematised workflows mean faster adoption. But they're not adequately distinguishing between process automation, which can adopt quickly, and judgement augmentation, which faces the same institutional resistance as everywhere else in legal.

The funding is going in before we have enough evidence to know which type of IP tool will actually achieve sustained embedding at scale.

That's the same pattern: capital moving faster than adoption evidence.

The Most Dangerous Assumption No One Is Questioning

The entire $10.59 billion is implicitly betting that lawyers and legal institutions will adapt—that they'll learn new workflows, trust machine output, change decision-making processes, restructure how work gets done.

But every pattern in institutional legal behaviour suggests the opposite: these environments don't adapt to technology, they absorb it into existing patterns or reject it.

What almost no one is questioning is whether these tools are being designed for the institutions that actually exist, or for idealised versions of those institutions that investors wish existed.

The funding is going to solutions that would work brilliantly if legal professionals behaved like early adopters in low-risk environments.

But legal institutions are late adopters in high-risk environments with extreme procedural inertia. The technology is being built for the wrong behavioural model.

This assumption is dangerous because it's invisible. No investor says "we're betting that law firms will fundamentally change how they work." They say "we're backing a solution to a clear problem."

But embedded in that framing is the assumption that problem recognition leads to behavioural change, and in risk-averse professional environments, it doesn't.

Problems can be acknowledged for years without triggering the workflow disruption required to solve them, because the cost of change—perceived risk, retraining burden, cultural resistance—exceeds the pain of the existing problem.

80% of corporate legal executives expect their outside counsel bills to be reduced as a result of AI technology. However, only 9% of law firm leaders reported that their corporate clients have expressed this expectation to them.

72% of in-house counsel predict AI will allow more work to be done internally. 70% of law firm leaders believe AI will enable them to offer new, value-added services.

Law firms and clients operate under mutually incompatible assumptions about AI's impact. The funded technology hasn't resolved the fundamental value proposition that would drive genuine adoption.

The $10.59 billion is funding solutions to problems that legal institutions agree exist, but it's not funding solutions that operate within the behavioural constraints those institutions actually exhibit.

And because that assumption is baked into the entire investment thesis, it's not being interrogated at the deal level.

Every pitch deck acknowledges that legal is conservative and slow to change, but then proceeds as if that conservatism is just a go-to-market challenge rather than a fundamental design constraint.

It's not a sales problem. It's an adoption architecture problem.

And almost no one is building for the institution that exists versus the institution they need to exist for their solution to work.

The Signal That Will Separate Success From Theatre

When this $10.59 billion eventually sorts itself into companies that achieved genuine adoption versus companies that sustained deployment theatre, the clearest signal will be retention behaviour at the individual user level, not at the account level.

Specifically: what percentage of users who had access in month six are still actively using the tool in month eighteen, and did usage frequency increase or decrease over that period?

Companies that achieve genuine adoption will show usage intensification over time—users log in more frequently, use more features, spend more time in the tool as it becomes embedded in their workflow.

Companies sustaining deployment theatre will show usage decay—initial experimentation drops off, logins become sporadic, users revert to previous methods whilst maintaining the licence because the firm paid for it.

Account-level retention obscures this because firms will renew contracts based on sunk cost, partner directives, or fear of being seen as behind on technology, even when actual usage is minimal.

But individual user behaviour doesn't lie.

If lawyers stop using a tool once the novelty wears off or once the implementation team stops checking in, that's deployment without adoption. If they increase usage as they discover the tool actually reduces friction, that's genuine embedding.

The pattern that will have predicted success is early evidence of usage persistence without external pressure. Companies that required constant customer success intervention to maintain usage were sustaining deployment theatre.

Companies where usage became self-reinforcing—where users started asking for additional features or training because the tool had become essential to their workflow—those achieved adoption.

In retrospect, the distinguishing factor will be whether the tool became the path of least resistance or remained an additional step that required conscious effort to remember.

Adoption means the tool becomes harder to remove than to keep using. Deployment theatre means the tool requires ongoing justification for why it's still there.

That difference shows up in individual usage persistence curves, and almost no one is measuring it properly right now.

We won't see a 2026 crash. We'll see a 2026-2028 sorting process where the gap between capital allocation and adoption reality gets resolved through consolidation, down rounds, and failures that get individually explained away rather than collectively understood as evidence that the entire funding surge was predicated on behavioural change assumptions that didn't materialise on the expected timeline.

The $10.59 billion proves that investors believe in the category. What it doesn't prove is that the institutions receiving these tools are ready to change how they work.

And that gap between belief and behaviour is where the next few years will sort the genuine adoption stories from the deployment theatre.